Who—or What—is Above the Law?

The presence and absence of religion in the Senate impeachment trial of President Trump

For the third time in this nation’s history, a President—Donald John Trump—has been impeached. Leading up to the impeachment, the phrase “no one is above the law” was invoked regularly. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, news commentators, and pundits of (almost) every stripe made that claim about the law’s supremacy. What is more, and maybe a problem for this President, ignorance of the law is not a valid excuse for breaking the law. And so, as former Iowa Senator Tom Harkin noted in an op-ed in the Washington Post, the Senators now function not as jurors but as a court that will, in the end, rule on this case.

Happily, for Sightings authors trying to catch a glimpse of religion in the hubbub of culture and society, something happened at the beginning of the impeachment proceedings that sparked reflection about the law, even though it was an event so common we rarely contemplate it.

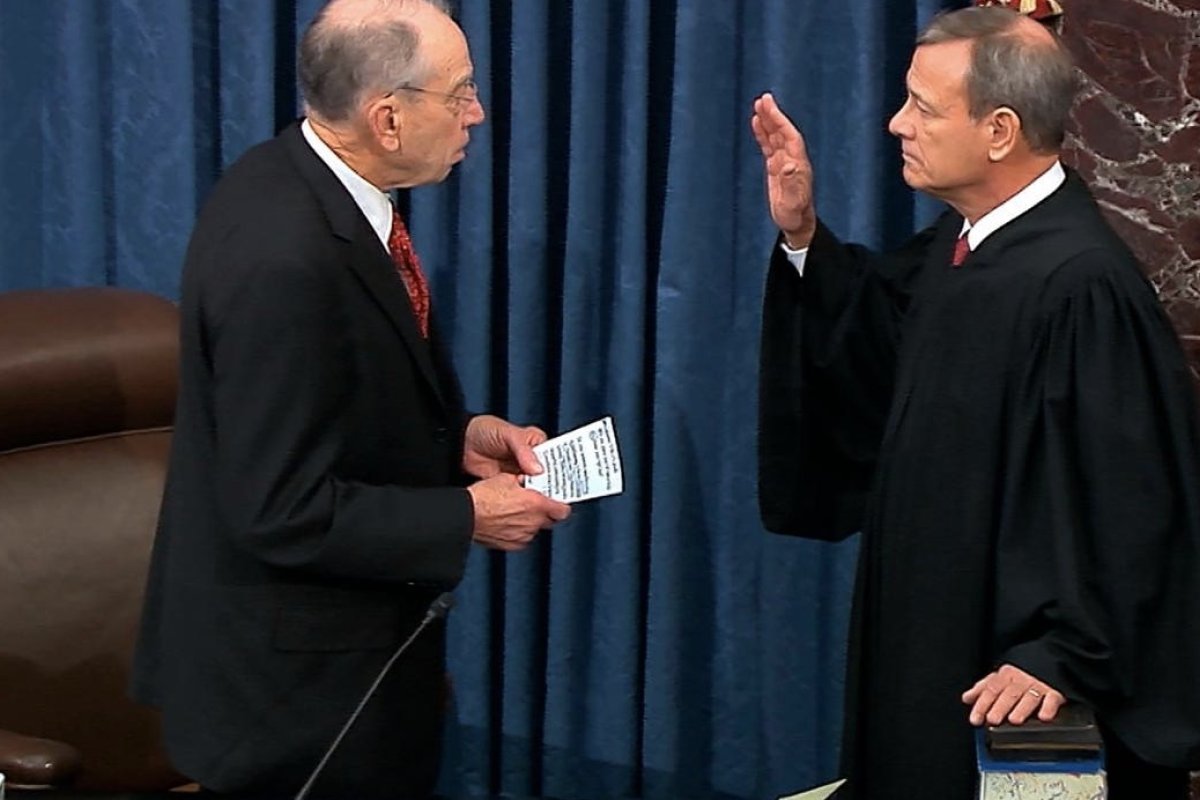

On the first day of the proceedings, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, John Roberts, was sworn in as judge of the trial by Iowa Senator Chuck Grassley, the President Pro Tempore of the Senate. In doing so, Roberts was asked by Grassley to place his left hand on the bible and to raise his right hand to swear his oath to administer justice with impartiality. In order to uphold the law and administer justice in accordance with it, the Chief Justice swore on the bible as a sign of truth.

Is the bible above the law?

Oath swearing is always a part of criminal trials, since perjury is a crime. In this case, however, it seems that not only the President but also the Chief Justice are on trial. Oath swearing is also present in civil law in affidavits, depositions, motions, and trials, but it is never made on a bible in these instances. The use of a bible seems to demonstrate the importance society gives to the event in addition to clearly signaling a warning against perjury. Impeachment is an occasion of the gravest importance to this country.

A few questions seem in order, questions that have dogged philosophers and theologians for centuries: the first question is about the source of the law; the second about what ensures its compliance (if anything); a third is about knowledge of the law.

Let’s start with some bits of history in order to get into these issues. One can recall that the sole reason Socrates, in the Crito, did not escape prison and his death sentence, even with ample opportunity to do so, was because, he argued, one must always follow the laws. In fact, he claimed that the laws spoke to him about how they had nurtured him. No law is unjust, he taught, even if, as Plato later argued, it can be unjustly used.

Surprisingly, Machiavelli, in The Prince, and Nietzsche, for all of his ranting about “slave morality” and its origins in religion, saw in Moses a great lawgiver and commander of forces. He was, Machiavelli claimed, a model prince where force and stealth can ensure compliance.

Natural Law thinkers, especially as articulated by Thomas Aquinas, argued that the human mind is created with the first principles of practical reason and in fact participates in the Eternal Law, the very mind of God. God’s law is knowable and promulgated in the human mind itself. Thomas Hobbes, mindful of the English Civil War (1642-51), not only developed the idea of a social contract, but he also argued that justice is simply what the Leviathan commands. Enlightenment thinkers of various sorts sought to ground law in the social contract itself, though differently understood.

And those ideas bring us back to Grassley and Roberts insofar as American jurisprudence draws on English common law and social contract theory and the possibility of perjury in criminal and not common law cases. It is “we the people” who are the origin of law enacted through our representatives, ignorance of the law is no excuse for noncompliance with it, and the state has the power of enforcement through various means, the most extreme being execution.

But why swear on the bible, especially when there is a separation of Church and State. After all, we live in a Republic that does not hold that God reveals the origin, force, or knowledge of the law in scripture or hardwires it into the human mind, no matter what some believe. (Let’s also not forget that the Founders, like Jefferson and Adams, had some problems with the mixing of religion and politics!)

The easy answer is “tradition,” one that descends from older English practice. Taking an oath to tell the truth by swearing with one’s hand on holy writ would mean that lying would endanger one’s soul. Perjury brought damnation—“Thou Shall Not Lie,” as the Decalogue has it. Since one cannot look into the mind and soul of a witness, the reminder of being watched by an all-knowing God ensures truth-telling and invokes a terrifying power to enforce it.

Yet, behind this theological idea is another ethical and psychological one that also has a long history. Throughout the ages, people have argued that without the fear of punishment and hope of reward people will not be inclined to fulfill their duties. In older times, atheists could not testify in court because they lacked the fear of damnation that would ensure honesty. More recently, Dostoyevsky put it bluntly and famously: if God is dead, then everything is permitted. Of course, that worry would seem to be empirically false. Lots of non-religious women and men are truthful and many religious people, well, fall short of their promises and duties. What is more, the bible is no longer needed, at least not officially. People in court can simply affirm that they will tell the truth and fulfill their obligations. In any case, fear of punishment and the hope of reward are hardly noble or even moral motives to fulfill an obligation.

Interestingly, The Hill reported in an article by Jordain Carney that “Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts administered the oath to senators, who were standing at their desks on the Senate floor with their right hands raised.” No bible there! Are we to infer that only Justice Roberts needed the fear of God put to him in order to fulfill his sworn promise and that Senators are naturally more given to administer impartial justice? That’s an odd (and probably false) conclusion given what some Senators have said about their participation in this trial! So, was this just an arcane rite put into service for Justice Roberts because of the rarity of this event? Who, if anyone, requested it?

Like many sightings of religion, we will probably never know the answer to why this specific appearance of religion happened. But also, like other sightings, the Chief Justice’s left hand placed on holy writ provokes reflection on the ordering of life in societies built on law with roots in religion. And if nothing else, that provocation of thought is for the sake of the common good.

Let’s hope that the Chief Justice and the Senators in this case about high crimes and misdemeanors—noted in Section 4 of Article Two of the United States Constitution on Impeachment—do in fact fulfill their promises. For our Republic claims to hold that nothing and no one is above the law. Let the laws speak to them of their duty. ♦

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.

Image: Senator Chuck Grassley swears in Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts ahead of the Senate Impeachment Trial of President Trump.