Sighting (and Citing) Chaplains

Exploring the growing role and significance of chaplaincy in American society

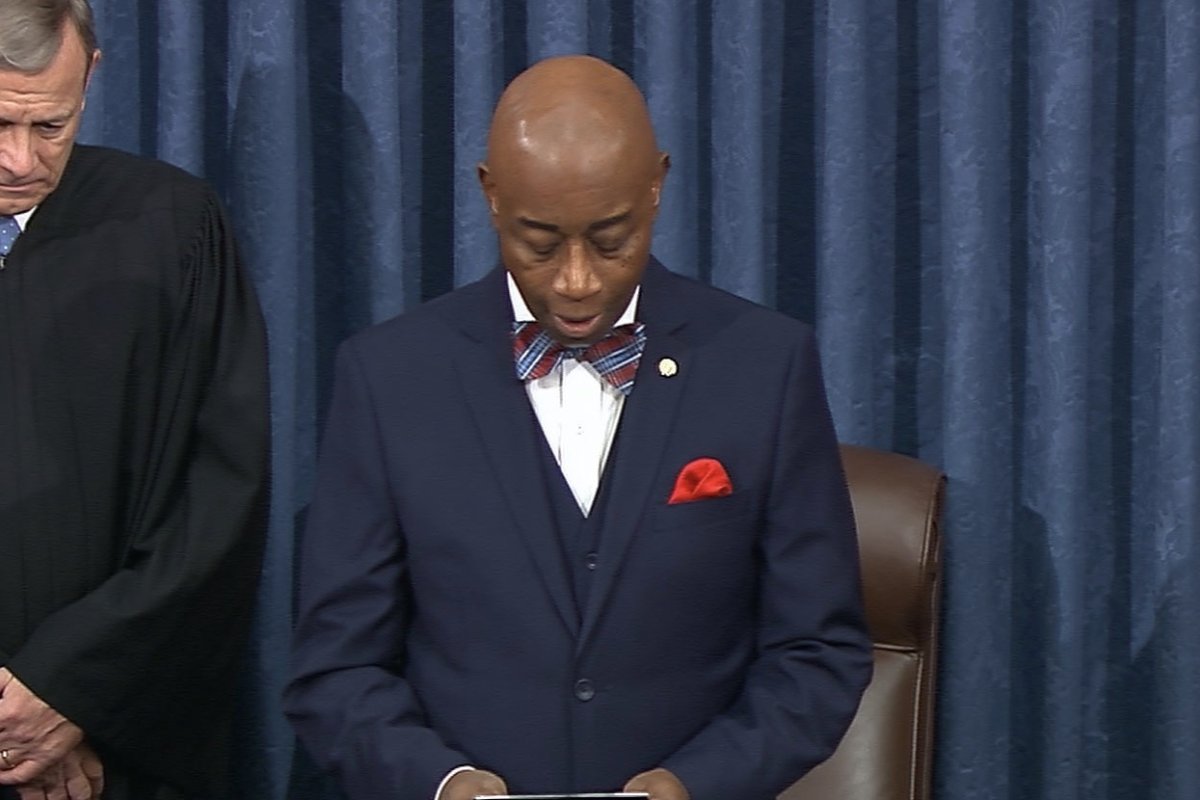

Amid the fractiousness of last month’s impeachment trial, news sources on both sides of the Atlantic found something to admire in a surprising place: the daily prayers of the Senate’s chaplain.

Rev. Barry Black has been the Senate chaplain since 2003. He is the first African American to hold the position and the first Seventh-day Adventist. Before assuming the Senate post he has held for twenty years, Black was the chief of Navy chaplains; he has doctoral degrees in ministry and in psychology.

During the last week of January, an article in The Nation dubbed Black “the stealth star of the impeachment proceedings,” noting the chaplain’s daily witness to civility, and his increasingly urgent appeals for Congress to engage their “cognitive capabilities and moral discernment for (God’s) glory.” The chaplain gave voice to the exasperation of a nation when he concluded his invocation on the morning of January 30 with these words: “Grant that they will comprehend what really matters, separating the relevant from the irrelevant.”

In the same vein, The Guardian’s headline echoed the words of Black’s prayer on January 31, the morning that Congress anticipated their vote on whether or not to call witnesses: “Remind our senators that they alone are accountable to You for their conduct,” he said. “Lord, help them to remember that they can’t ignore You and get away with it. For we always reap what we sow.” Delivered in Black’s resounding baritone and dignified cadence, these prayers seemed to transcend sectarian language and partisan finger-pointing, sounding the depths of the occasion and calling his hearers to engage this rare opportunity for discernment with gravity and humility. As The Nation’s Elie Mystal observed, “Even atheists and non-spiritual people could draw moral strength from Chaplain Black’s impeachment trial performance.”

The role of the Senate chaplain is not a new one. There have been chaplains in Congress since 1789, although the position was only made full-time in the middle of the twentieth century. This embodiment of religious practice inside the halls of government has not been without its critics: the appointment of congressional chaplains and the practice of prayer in governmental spaces has been the subject of numerous court cases. The constitutionality of legislative chaplains was upheld in 1983 by the Supreme Court—Marsh v. Chambers—on the grounds of precedent and tradition. Explaining its ruling, the Court observed that the use of prayer “has become part of the fabric of our society,” coexisting with “the principles of disestablishment and religious freedom.”

This constitutional complexity of our communal fabric—as it stretches towards the improbable possibility of a society at once freed for, and from, religion—maintains the lively tension out of which this interstitial profession of chaplaincy has grown and continues to evolve. Originally tasked with providing religious rites and services for persons unable to access their communities of faith, such as military personnel, hospital patients, and incarcerated persons, the profession has expanded its vision and extended its reach over the past fifty years. Increasingly, these shepherds are tending the wild spaces between our native abilities to cope and the onslaught of changes that are formidable, inevitable, and ubiquitous, in hospital rooms and trauma centers, on university campuses and in prisons, in airports and corporate cubicles, as well as in Congress.

Today’s chaplains still provide access to familiar spiritual practices, but for those whose experience is not informed by formal religious institutions and practices, chaplains are an attentive presence, an advocate for dignity and wholeness, or a compassionate guide in the process of grieving losses and relearning the world.

Sondos Kohlaki Kahf, a Muslim chaplain, refashions the etiology of the word itself to describe this work: “In studying chaplaincy, I learned that the word ‘chaplain’ evolved from the Latin word, ‘cappa,’ or cloak. I thought of all that the cloak symbolizes: warmth, protection, security, and concealment, and how all those qualities overlap with what a chaplain aims to provide for the careseeker. And then I was struck by the story of Khadija (R), when she covered the Prophet (S) with a cloak after he returned from his retreat terrified and confused. In that moment of distress, Khadija (R) comforted and supported him. She ‘chaplain-ed’ him, the one from whose perfect example our pastoral care strives to emulate.”

Such practical innovation is inspiring seminaries and divinity schools, once focused almost exclusively on preparing congregational leaders, to develop courses of study for chaplains. Agencies and entities that supervise and certify chaplains are renovating their requirements so as to recognize chaplains from a wide variety of faith communities, as well as secular, humanist, and atheist caregivers.

How are we to account for this flourishing species of spiritual leadership, growing up through the cultural “cracks” between sacred and profane, church and state? What felt needs are being met (and being cultivated, for that matter) by these providers of nonsectarian care? What can we learn about the state of the American soul?

Some religion scholars suggest that the decades-long decline of organized Christianity and its congregational life in the U.S. has weakened our culture’s resources for meaning-making, creating a societal need for the individualized crisis care chaplains provide. Others point to our country’s increasing plurality and the unlikely sponsorship of diverse religious expression by secular and governmental organizations that are required to provide services equitably, including religious ones. Neither of these explanations, however, account for the mounting moral anxiety and spiritual hunger in so many secular spaces—the legacy, perhaps, of an unbridled capitalism that brings with it crises of being and meaning throughout our common life, in education and health care, in criminal justice and government, in the sciences and in the marketplace.

At their best, chaplains are present in these “thin places” where human beings and human dignity are most vulnerable. They recognize, name, prioritize and attend to vulnerability, both individual and collective. By engaging careseekers in lived and lively theological reflection that responds to human need, rather than being driven by an apologetic, ecclesiastical, or sectarian agenda, they seek to restore some measure of agency and hope to those who suffer. Congregations that struggle for significance in the present moment might look to these chaplains’ example of spiritual companionship amidst the messiness and complexity of life.

At the same time, as Chaplain Black can attest, when such services are hired and paid by the marketplace or the state, chaplains may find themselves serving unreliable masters if they themselves are not rooted in communities of study and practice. Warfare, incarceration, and health care desire compliance from their populations, and religion can too easily be deployed as a tranquilizer for difficult cases, a pacifier for uneasy consciences, or a finger on the scale for the status quo. Chaplains must inhabit their complex roles in the world with a healthy sense of skepticism about the powers by whom they are authorized and employed, while communities of faith must follow the impulse of chaplaincy to engage those same powers, at the precipices of human pain.

It is no simple thing to create and maintain communities, institutions, and governments that keep us all free from coercion, and free for flourishing. The stress fractures and fault lines in these associations are all too obvious—no single ideology, profession, or political party can comprehend the complexity of human need or plumb the limits of human possibility. Bearing witness to our collective failures, naming the limitations of our imaginations and wills, and holding space for repentance, reflection, and renewal is the work of spiritual caregiving in today’s public arena. Chaplains and faith communities alike must call our constituents to “comprehend what really matters, separating the relevant from the irrelevant” by means of our presence, our intention, our advocacy … and our prayers. ♦

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.

Image: Senate chaplain, Rev. Barry Black, reads a prayer during impeachment proceedings as Chief Justice John Roberts looks on. (Photo: Senate Television)