How War Bypasses Morality

Examining how wartime decisions often end up violating our ethical beliefs about war

“We took action to stop war, not to start it,” President Trump said in his recent statement about the attack against Qassim Soleimani. This statement sounds hauntingly familiar. The president’s speech echoes previous wartime rhetoric, rhetoric which has a tendency to distort our moral judgments. As the nation discusses the ethics of this strike and possible next steps, it is worth taking a moment to remember how the discourse that surrounds war can bypass our consciences.

Psychologist Albert Bandura argues that our ordinary moral rules and religious commitments, even when sincerely affirmed, often fail to prevent us from justifying immoral actions in wartime. He writes, “Moral standards ... do not come into play unless they are activated, and there are many social and psychological maneuvers by which moral self-sanctions can be disengaged from humane conduct.” Bandura calls this phenomenon “moral disengagement.” Let’s survey four forms of moral disengagement that are likely to happen more in the coming months.

Moral framing and euphemistic labeling. People tend to frame their own actions in morally neutral or positive ways and to use euphemistic language that does not trigger moral red flags, thereby making it difficult for moral rules to restrain behavior. “People do not ordinarily engage in harmful conduct,” Bandura writes, “until they have justified to themselves the morality of their actions.” People innately search for justifications, and tend to justify immoral means by framing their actions solely in terms of ethical ends. Hence, a person morally averse to bombing civilians might nonetheless approve of the bombing of civilians if the action is framed as “fighting terror” or “stabilizing a region.”

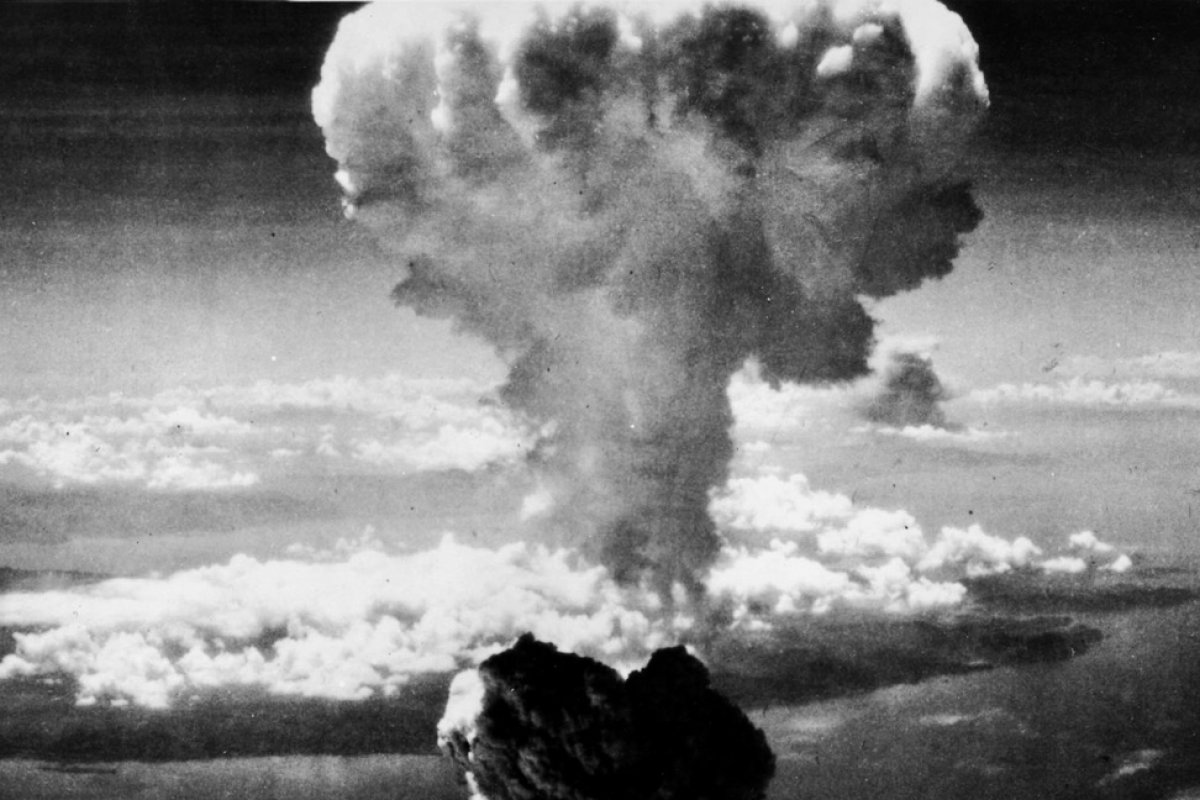

This tendency causes problems because an action can be described in many different ways, each of which carries different moral significance. G.E.M. Anscombe gives as an example the self-deception that occurred when Nazi executioners framed their actions in morally positive terms like “following orders.” Similarly, many Americans did not fully grapple with the morality of dropping atomic bombs on Japan because the bombings were framed in terms of “ending the war.” When descriptions of this sort are used, people’s moral prohibitions against killing noncombatants are not “activated,” to use Bandura’s term.

The activation of moral rules is inhibited by the use of euphemistic language. A person who believes that torture is morally wrong, for example, might not have that commitment activated if torturous acts are labeled “enhanced interrogation.” Because the terminology is different, people are not confronted with the fact that they are approving and disapproving of the same behavior at the same time. When people (like Soleimani) are described only as “terrorists,” our usual moral inhibitions about killing foreign leaders might not activate.

Advantageous comparison. A second form of moral disengagement is advantageous comparison, the tendency to exonerate one’s own behavior by contrasting it with other people’s behavior. Just as a patch of color in a painting looks brighter or darker depending on the colors that surround it, so an action will look more or less morally justifiable depending on the actions to which it is compared. In conflict, these comparisons are usually with the prior actions of one’s own side, with the imagined alternatives, or with the actions of the opponent.

If an action is seen as in line with one’s previous actions, it’s less likely to provoke self-examination. When a course of action is seen as standard operating procedure, people typically refrain from considering its morality. If we’ve done it before, then this new action is seen as the unfolding of an existing policy and not so much a new decision that requires further justification.

A second form of comparison is when one compares an aggressive course of action favorably to a more restrained course of action. As Bandura notes, this comparison in war often leads people to favor greater violence. Regardless of the projections of experts, people assume that applying greater force leads to more positive outcomes than applying restrained force. More frequently than this, however, people compare a candidate course of action with total inaction. Leaders in a military conflict may approve of a military action because, while it may not be morally perfect, it is better than doing nothing. These comparisons serve to make a morally objectionable action seem like the only viable option. This makes the act of choosing to pursue this action feel like it is not a real choice; in the absence of a felt decision, it does not activate moral self-examination.

More interesting, perhaps, is when an action is compared to the actions of the enemy. If the enemy is already relying on immoral means, people are more likely to deem it fair and even necessary to follow suit. Though in theory this means conflicts would not escalate in immorality since no party wants to do something more ruthless than the opposition, in practice it has the opposite effect. Because of self-selecting bias, each side sees its enemies’ actions as unjustified aggression but sees its own actions as justified responses. Thus, “by exploiting the contrast principle,” Bandura writes, “reprehensible acts can be made righteous. Terrorists see their behavior as acts of selfless martyrdom by comparing them with widespread cruelties inflicted on the people with whom they identify.”

Displacement of responsibility. Summarizing the findings of Stanley Milgram’s famous study, Bandura writes, “People will behave in ways they typically repudiate if a legitimate authority accepts responsibility for the effects of their conduct.” Following an authority is another way people make choices without registering to themselves that they are making choices, thereby temporarily avoiding the felt need to reflect on the morality of their actions. Whether explicitly following a leader’s orders or more generally following the leader’s example, the moral burden is placed on another person, so an individual does not compare their own actions to their moral commitments. Tragically, an entire society can rely on displacement of responsibility to shield themselves from moral scrutiny. Citizens shift the responsibility to the president, the president shifts it to advisors, advisors shift it to constituents, and so on. Decisions are made and justified without anyone ever having the sense of a moral threshold being crossed.

Attribution of blame. People morally disengage from their actions by blaming their adversaries. “In this process,” Bandura writes, “people view themselves as faultless victims driven to injurious conduct by forcible provocation.” One’s actions are treated as mere reactions, caused not by one’s own decisions but by the actions of the enemy. Attribution of blame can either be done consciously, to justify harmful actions as necessary, or subconsciously, to overlook one’s agency and bypass the need for justification.

As Bandura notes, attribution of blame is often invoked by both sides in a conflict, contributing to a phenomenon called “reciprocal escalation.” Each side understands its own actions as necessary reactions to the other side’s provocation. Hence, in modern warfare, it is not uncommon for each participant to view their involvement as a defensive struggle, merely responding to the other side’s aggression. Because the other side started the war, it is argued, they are to blame for setting in motion a chain of events that includes our own punitive reactions. If our actions are excessive or barbaric, it is the other side’s fault for driving us to such extremes.

We see this happening in the justifications some Americans, Iraqis, and Iranians have given for the escalating threats and violence in the past few weeks. Each action is described as a response to prior aggression; Iranian president Hassan Rouhani tweeeted, “the path of resistance to US excesses will continue. The great nation of Iran will take revenge for this heinous crime,” while President Trump tweeted, “They attacked us, & we hit back.” In wartime, this reciprocal blame ultimately leads to an erosion of responsibility.

These four “maneuvers” help explain why affirming moral rules—for example, those of qital or the just war tradition—is no guarantee that one will act accordingly. Ironically, it is in times of crisis when we can be least critical, least likely to step back and compare our words and actions against our moral convictions. Being aware of the ways our consciences get bypassed by moral disengagement can protect us from unwittingly violating our ethical and religious commitments in conflict. ♦

Image: Atomic Cloud over Nagasaki, August 9, 1945.

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.