God Bless You Please, Mr. Robinson

On April 25, 1719, the English-speaking world was first introduced to The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner ..

On April 25, 1719, the English-speaking world was first introduced to The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner ... Written by Himself. The immediate reception of this book must have been strange and surprising first and foremost to its author, Daniel Defoe, as he managed to achieve what many writers, even our most cherished, are denied: a fame that can be experienced in one’s own lifetime—especially on the basis of one’s first appearance in print. Before the calendar turned to 1720, Defoe’s book had already gone through four editions, and by the time of his death twelve years later he would witness his protagonist inspire a host of imitators and re-imaginings. And if exegetical variety is any index of literary achievement, then Crusoe the figure stands out for the diverse ways in which he has come to be interpreted and metonymized: inter alia, as a preeminent representation of modern individualism (Ian Watt); the archetype of the British colonialist attitude (James Joyce); and the incarnation of unfettered capitalist acquisition (Karl Marx).

On April 25, 1719, the English-speaking world was first introduced to The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner ... Written by Himself. The immediate reception of this book must have been strange and surprising first and foremost to its author, Daniel Defoe, as he managed to achieve what many writers, even our most cherished, are denied: a fame that can be experienced in one’s own lifetime—especially on the basis of one’s first appearance in print. Before the calendar turned to 1720, Defoe’s book had already gone through four editions, and by the time of his death twelve years later he would witness his protagonist inspire a host of imitators and re-imaginings. And if exegetical variety is any index of literary achievement, then Crusoe the figure stands out for the diverse ways in which he has come to be interpreted and metonymized: inter alia, as a preeminent representation of modern individualism (Ian Watt); the archetype of the British colonialist attitude (James Joyce); and the incarnation of unfettered capitalist acquisition (Karl Marx).

Alongside the slew of articles (both laudatory and critical) marking the occasion, the three-hundredth anniversary of the release of Robinson Crusoe will be commemorated next week in York by the sixth biennial convening of the Defoe Society. Yet what makes the tercentenary worthy of attention in a publication like Sightings is not its worldly success, its grip on the popular imagination as a beloved adventure story, nor its for now secure placement in the Western, British, or novel canons. For what is oftentimes overlooked in considerations of the work, and must therefore be stressed, is its explicitly religious character and the specifically Christian register of its narrative voice. Even its conventional classification as a “novel”—arguably the first of its kind in the English language—belies the fact that the work is structurally indebted to the classical genres of confession and spiritual autobiography. Defoe’s own theological convictions, of some ironic distance to those held by his narrator, are beside the point here. What is of interest is the way in which events are at one and the same assimilated by Crusoe the storyteller into a distinctly religious framework and are informed by a distinctively Christian paradigm.

Apart from the book’s religious substratum, it constitutes an apposite subject for a publication devoted to communicating “sightings” of modern religious life because its main character specially embodies the metaphor of the publication’s title. As much as Crusoe may demonstrate the virtues of diligence and industriousness, and may manipulate his man Friday to promote his own drive for sovereignty, he is at bottom a discerner, one who “sights” inside and out, and who continually tries to make sense of the one on the basis of the other. For example, the animating impulse in response to his shipwreck on an uninhabited island near the Orinoco river is not lament or self-pity, but an effort to grasp his situation. Is his punishment due to a state of unresolved sin? Has it been caused by the dereliction of his divine calling? Or is it rather a result of violating the demands of filial piety and obedience by deciding to pursue the seafaring life? The answer, of course, is neither crucial nor susceptible of discovery. What is significant is that his misfortune is never taken at face value but is understood to have supernatural causation and design. Events, in other words, are always “symbolic” insofar as they point to a divine intention, and Crusoe’s narration is a sustained attempt to descry their purpose for him.

Furthermore, it is Crusoe’s dissatisfaction with the visible—his insistence that meaning lies beyond the given—that enables him to translate misfortune into blessing, to shape and re-shape events auspiciously even as they oppressively shape him. The “discovery” that his fate is by no means a sign of God’s abandonment but is instead proof of His benevolence, is what first allows him to reclaim the sense of himself as an actor who can fashion outcomes in his favor. It is this perceptual and attitudinal transformation that necessitates the first-person narration, for the reader must be taken into Crusoe’s mind in order to observe the counterintuitive logic of his thinking. On the other hand, the first-person account creates a situation in which a providential governor never appears but is only invoked. The immediacy of an intervening God as depicted in Scripture is replaced by a teller who orders and relates the story of his life once he understands its full meaning.

Perhaps dimly in the background of a story that moves from misfortune to fortune is Martin Luther’s theologia crucis, centered on the idea that temporal suffering is sub paradoxis a sign of divine election as well as the surest way of confirming one’s eternal salvation. Yet the primary theological foundation supporting Robinson Crusoe is John Calvin, who, in marked contrast to Luther, claimed that divine blessing manifested itself in material success—a principle which both confirms and motivates a certain kind of human behavior. Yet if the book were simply a dramatization of certain strands of Reformation theology, then its appeal would not extend outside the circle of papal dissenters. It is the following passage by Clifford Geertz on the nature and endurance of the religious consciousness that lends the work a wider appeal and makes a claim on us as beings who are fundamentally preoccupied with what he calls “the problem of meaning”:

The strange opacity of certain empirical events, the dumb senselessness of intense or inexorable pain … raise the uncomfortable suspicion that perhaps the world, and hence man’s life in the world, has no genuine order at all. … And the religious response to this suspicion is in each case the same: the formulation, by means of symbols, of an image of such a genuine order of the world which will account for, and even celebrate, the perceived ambiguities, puzzles, and paradoxes in human experience. (23)

Crusoe remains a vivid and perduring exemplum of the virtually inextinguishable effort to make sense of suffering, to cope with and even resist chaos by the superimposition of cosmos. More basic than making life worth living, these meaningful constructions serve to make it livable.

So, on this festive occasion, forget the cake, drop the perfunctory singing, and spare yourself a trip to CVS for the humorous Hallmark card. Instead, simply take up and read, and you will grant Crusoe’s wish.

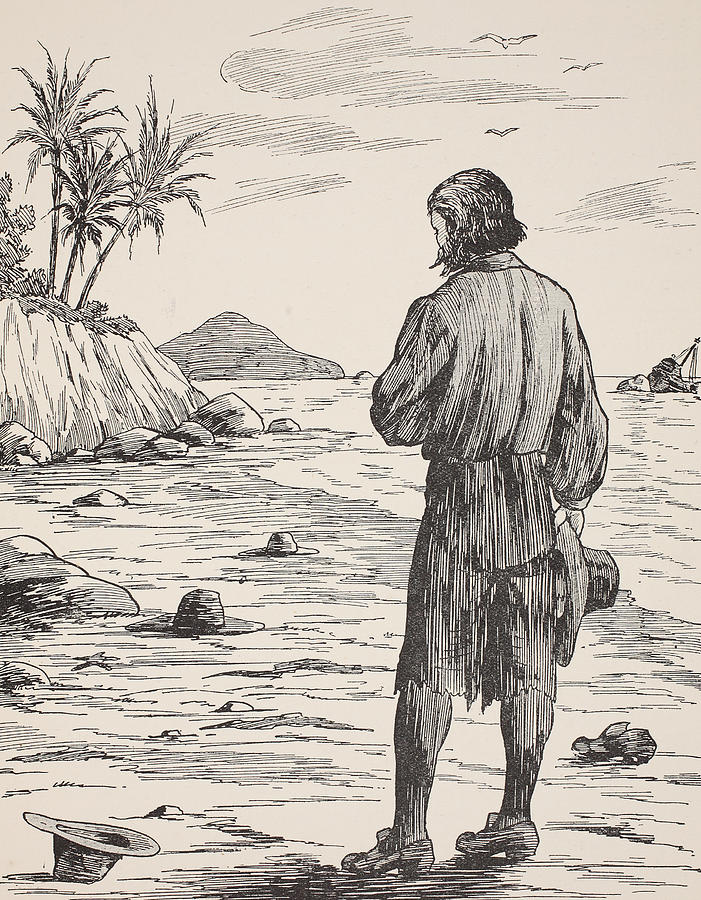

Image: “Robison Crusoe on His Island,”, illustration from The Story of Robinson Crusoe: An adaptation for children following Defoe's language.

Author, Matthew Creighton, is a doctoral candidate at the University of Chicago Divinity School in the field of Religion and Literature. He is currently writing a dissertation on the literary representation of father-son relations among German-Jewish authors. His contributions to the discipline can be found in Religion and the Arts, German Studies Review, and Religious Studies Review. Author, Matthew Creighton, is a doctoral candidate at the University of Chicago Divinity School in the field of Religion and Literature. He is currently writing a dissertation on the literary representation of father-son relations among German-Jewish authors. His contributions to the discipline can be found in Religion and the Arts, German Studies Review, and Religious Studies Review. |

Works Cited

Geertz, Clifford. “Religion as a Cultural System.” In Anthropological Approaches to the Study of Religion, edited by Michael Banton, 1-46. New York: Routledge, 2010.

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD candidate in Religions in America at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.