The Art of the Social Contract

The art that is helping us see the failures of America's social contract

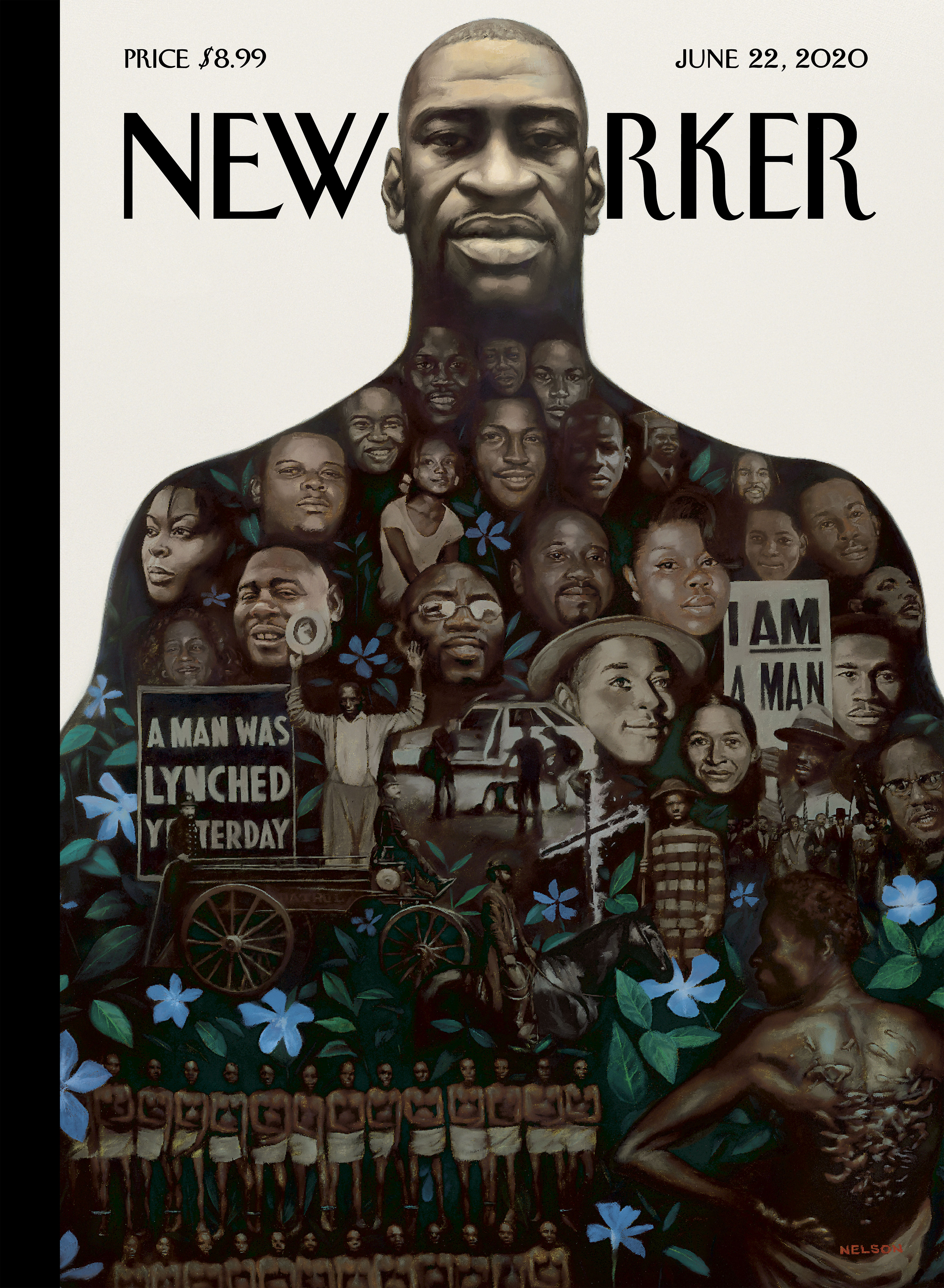

It has been remarked that the most profound interpretation of a work of art is another work of art. One case in point is Kadir Nelson’s June 22, 2020, New Yorker cover, “Say Their Names,” in which Nelson portrays individuals and groups who were victims of racism in an aggregate that configures the body of George Floyd. (The New Yorker website includes an on-line “walk through” that details these individuals and groups, and in doing so renders the drawing a kind of “visual culture” complement to the “1619 Project.”) Borrowing from Walt Whitman’s epic “Song of Myself,” Floyd is made by Nelson to contain multitudes.

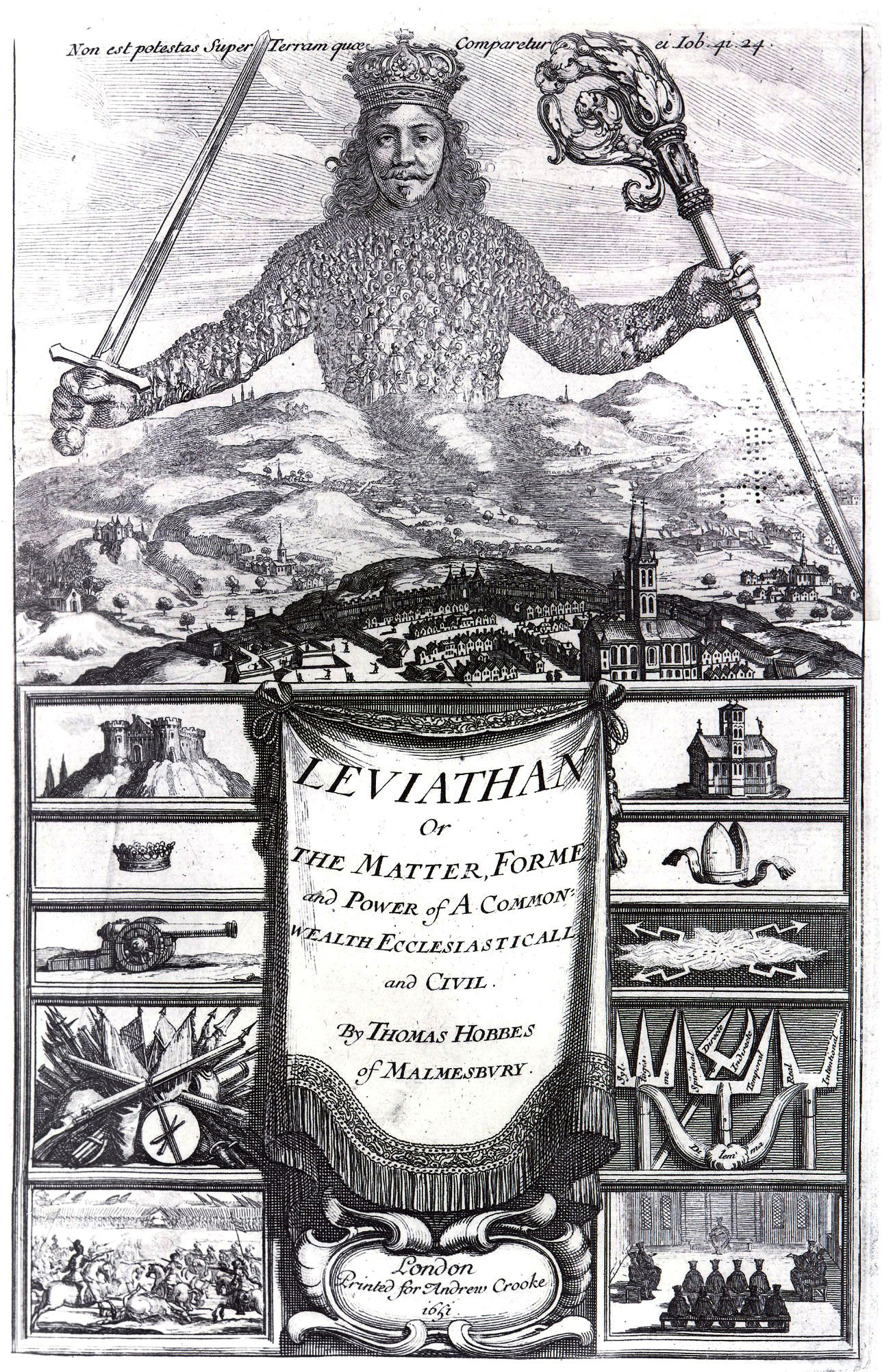

Nelson’s chief allusion here is not, however, to Whitman but to the frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651). The inaugural English-language text of social contract theory, Hobbes chose to precede his own words in Leviathan with an etching composed by the skilled artisan, Abraham Bosse. Hobbes debated with Bosse at length about its composition, and with continual ambivalence regarding one crucial detail. Their exchanges suggest that Hobbes took the frontispiece as an opportunity to encapsulate visually his ideas about the social contract in a way that went beyond even his own considerable capacity with words.

Bosse’s frontispiece presents in its lower center the book’s title (“Leviathan, Or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiastical and Civil, by Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury”). Above it, claiming the eye’s immediate attention, is the (somewhat bulky) figure of a torso, head attached, with arms outstretched and hands grasping, respectively, a sword and a bishop’s crozier. The body of this figure is comprised literally by the people of the nation.

Hobbes clearly intended the engraving to illustrate his conception of the social contract. The Sovereign should be, for Hobbes, a composite of the multitude of men [sic], whose identity as a social order is contractually affirmed in their consent to be so represented. Citizens give their consent because they commonly acknowledge that such a contract is superior to what preceded it, namely, a “state of nature” characterized by “all against all.” The relative freedom of the social contract is an improvement upon the “nasty, cold, brutish, and short” condition that came before.

Nelson’s drawing invokes and then immediately inverts Hobbes’s rationale. Where Hobbes’s sovereign is in the background of an accompanying set of contextual allusions, the figure of George Floyd is foregrounded and affords within himself all the necessary context. The figures who comprise the sovereign in Leviathan have their backs to the viewers as they look up to the Sovereign; the faces and bodies that comprise Floyd’s torso, particularly its upper half, look outward with a range of expressions, with Floyd’s face in indeterminate but ineluctable relation to them. Floyd’s arms are not articulated, but two signs balance his torso (“A MAN WAS LYNCHED YESTERDAY” on the left, and “I AM A MAN” on the right). Nelson anchors Floyd’s torso not with the drawing’s title but with a depiction of the beating of Rodney King by four Los Angeles police officers in 1991. Taken together these details underscore Nelson’s overarching inversion: in Hobbes’s frontispiece, the citizens are anonymous and uniform in aspect, while in Nelson’s drawing they are particular in aspect and unified by the common history of being black and thus the objects of racism. Nelson’s citizens have experienced not a state of nature but a state of sovereignty that has been nasty, cold, brutish, and all too short. Hobbes’s frontispiece represents an idealized sovereignty; Nelson’s drawing represents one distressing and ongoing effect of actualized sovereignty.

Nelson’s drawing indicts the ostensive American social contract. At this point Nelson’s implicit appropriation of Whitman becomes apparent: “Song of Myself,” when the singer is black, is a decidedly different litany of the land.

Adding further import are two considerations, one concerning Nelson’s agency, and one Hobbes’s. Nelson deletes from Hobbes’s frontispiece not just the previously noted arms but the blocks on which the sovereign community and its head rests, hinted at in the full title of Leviathan: the civil and ecclesiastical communities. For Hobbes, the commonweal was established and promulgated through law and religion. (Hobbes had complexly ambiguated views on religion and its relation to law, but the frontispiece and, in the end, the text of Leviathan affirm this view.)

Also, Hobbes considered two possible frontispieces for Leviathan. In the version Hobbes chose, as noted above the citizens have their backs to the viewer and look up with unified affect to the head of state. In the version Hobbes finally—but after some debate—rejected, the citizens face the viewer and look out with diverse affects, away from the head of state. The effect of the rejected rendering is still different from that of Nelson’s drawing, but it testifies to the apparent ambiguity in Hobbes’s mind that implies recognition of the complexities of the relation of sovereignty to citizenship.

Nelson’s appropriation of Hobbes also can remind us that Hobbes formulated his idea of the social contract in his own extraordinarily perilous moment, when questions of national identity, sovereignty, and the role of religion and the law were under complementary duress: the era of the English Civil War, launched with the beheading of a sovereign and carried forward by Oliver Cromwell for eighteen years via a Parliament whose membership exercised one of two options: sycophancy, or resistance. Nelson’s creation is thus at least triply appropriate, speaking as it does for the acute reality that the black experience calls into serious question the ideal of the social contract, for the (overly) confident celebration by Americans of e pluribus unum, and for its recourse to the visual to speak more fully than words to the enormities that mark the specifics of our time and place.

Images: Feature: Kadir Nelson painting "Say Their Names" (Photo Credit: Dr. Jungmiwha Bullock); Second: The New Yorker cover for June 22, 2020, "Say Their Names," by Kadir Nelson; Third: The frontispiece for Leviathan (1651) by Thomas Hobbes, etching by Abraham Bosse.

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.