American Graphic

Graphic novels, the national narratives we tell, and the role religion plays (and doesn't) in them

America has a near unquenchable thirst for imaginative narrations of its national identity. We like to tell ourselves stories about US. This process of reflection is often revisionist, can be clarifying or distorting, and often shapes, accurately or inaccurately, understandings of the nation’s history. This has resulted in distinctive national traditions of (only the most conspicuous examples) the novel and the cinema. One can achieve a remarkably nuanced perspective on the Civil War, for example, by reading in chronological sequence Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (1850), Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1856), and Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868-69). One can think deeply about the American era of “Reconstruction” by viewing D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915) and then reading the novels of Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright, William Faulkner, and Ralph Ellison. The American frontier comes to vivid and complex life in the evocative prose styles of Willa Cather and Laura Ingalls Wilder and unfolds before us via John Ford’s skilled camera lens and his consummate direction of such icons of American masculinity as John Wayne and Jimmy Stewart.

The last two decades has witnessed a new tradition that deploys in tandem these exemplary written and visual cultures. The graphic novel, a worldwide phenomenon like the novel and the cinema, has been appropriated and afforded a distinctive American cast. The “American Graphic” was announced forcefully by two already classic expressions: Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1991) and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home (2006). Many discussions of these texts describe them as “graphic novels” to underscore their narrative force and their historical engagements: Spiegelman’s with the legacy across generations of the Holocaust for American Jews, Bechdel’s with the questions of sexual identity worked out (or not) within the conventional American family. It is important to note that to engage these texts is not just to read them but to view them: the artistries of Spiegelman and Bechdel encompass both the written and the visual. Much of the power of their work resides in a graphic counterpart to musical contrapuntality—word and image move forward together, sometimes consonant and sometimes dissonant, each ever modulating the other.

What Spiegelman and Bechdel inaugurated is fast becoming, indeed has already assumed the position of a third strong and independent tradition of American narrative. Two recent examples from this burgeoning and compelling genre invite us to rethink salient aspects of our own cultural moment by thinking hard about what religion is and is not in contemporary America.

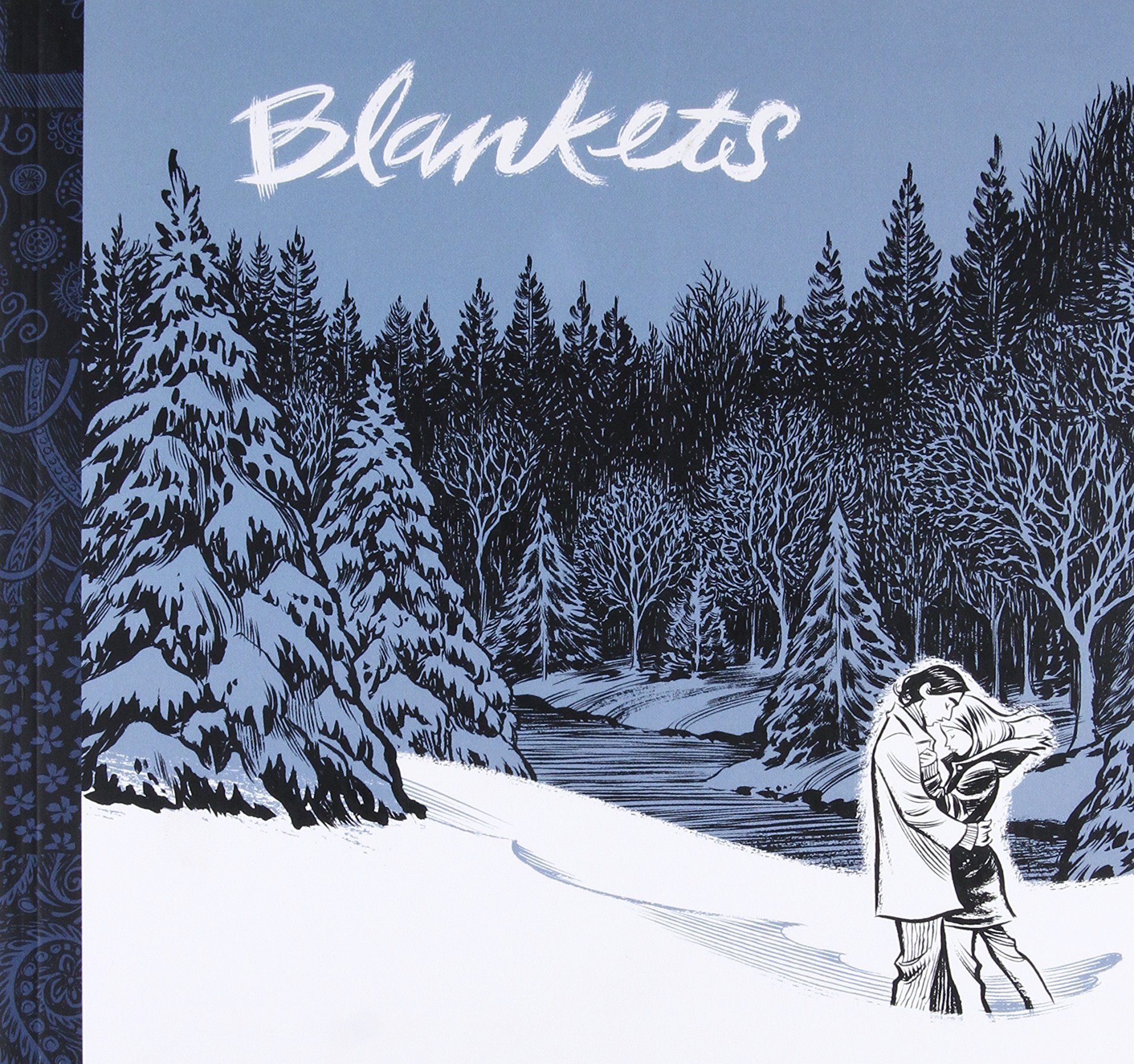

In Blankets (2003), Craig Thompson portrays the experience of a white, male, teenaged evangelical Christian whose disinterest in and suspicion of ecstatic religious experience is directly juxtaposed with his desire for and optimism about ecstatic romantic experience. The text is an autobiography and a form of confession, its own kind of heterosexual “coming out” story (Thompson used the book to inform his parents of his departure from evangelical Christianity). Blankets is self-reflexive in its examination of artistic creativity—the pages “enact” the mode of composition, showing how mere dots can morph into lines and then, in turn, into images—and the ways that the author’s creativity is itself a divine gift that his religious tradition fears and attempts to dissuade him from pursuing. The artist’s disenchantment with religion is not the only disappointment he relates, but the affirmation of drawing as at once a form of creation—and the wellspring of a range of virtues that his religion has failed to inculcate—affords an unmistakable and negative commentary on a specific variety of American religious experience that has a particular purchase on twenty-first-century America.

Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese (2006) examines the American assumption, or perhaps better, presumption of assimilation, through three apparently distinct narratives. Yang intersperses the classic Chinese narrative of the Monkey King (most recently translated in Anthony C. Yu’s Journey to the West) with the story of Jin Wang, a first-generation son of immigrants who has recently moved from San Francisco’s Chinatown to a suburban neighborhood, and also with the story of Danny, a white American boy whose time is vexingly marked by annual visits from a Chinese cousin who overtly and un-self-consciously embodies American racial stereotypes of Chinese. What links these stories is the theme of the stereotype, seen at once as social construct and as fundamental to identity formation. The book is one of the richest discussions known to me of the whats and the whys of clichés. The illustrations mimic American television in all its reductive capacities, so that word and image juxtapose the enduring place of Taoism in American culture.

Thompson and Yang each write autobiographically in the service of writing diagnostically—they draw on the specifics of their experiences to offer what is at once an interpretation and a critique of American life and the role that religion does and does not, and should and should not, play in it. If we group these two works together as we group those invoked earlier around the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the frontier, we see in these very different works at least three common themes: the individual as a microcosm of the nation, religion as inheritance, and the nation as decidedly interested party to that inheritance. The elders who urge Thompson away from art and toward ministry drive a wedge between forms of inspiration that force upon him a choice; his religion, or at least the religion in which he was raised, loses. The Tao that Jin Wang cannot discard, despite his most determined efforts to assimilate, forces upon him a recognition that only in leaving his home is he truly able to find it.

Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” (1930) proved to be a signature piece of Americana and, not at all incidentally, the source of a complex reception: its enthusiastic appropriation in museums had its counterpart in local outrage among the Iowans whom it was understood to depict and who felt it rendered them unsophisticated. The American Graphic as it emerges in the works of Spiegelman, Bechdel, Thompson, Yang, and many others will surely prompt a similarly complex and endemically American phenomenon: narratives of the nation, of US, that are read and that read America in return. ♦

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.