The Great Notice-er

Editor’s Note: This month we are celebrating both the twentieth anniversary of the Martin Marty Center and the ninetieth birthday of Martin Marty

Editor’s Note: This month we are celebrating both the twentieth anniversary of the Martin Marty Center and the ninetieth birthday of Martin Marty. Marty would say that our focus ought to be on the Center, not on him, and for the most part it is. However, Marty has also said that part of the mission of Sightings is to help “interpret the interpreters” of religion in public life, and for the past half-century and more there has been no more notable interpreter of religion in American public life than Martin Marty. So we took the occasion to put together a series of reflections on Marty’s unique contributions to the public understanding of religion from authors who are themselves leading interpreters—whether in academia or in popular media. Here is the second, with others to follow.

In his ninety years, Martin E. Marty has doffed many professional hats: pastor, professor, author, peripatetic lecturer, columnist, and occasional reporter. But I think of him principally as the greatest notice-er I’ve ever met.

In his ninety years, Martin E. Marty has doffed many professional hats: pastor, professor, author, peripatetic lecturer, columnist, and occasional reporter. But I think of him principally as the greatest notice-er I’ve ever met.

At the end of the Sixties, Marty was the first to notice that teens and twenty-somethings were wearing crosses, stars of David, and crescent moons along with various New Age symbols all on a single chain around the neck. It was an early sign of the spiritually promiscuous times to come. He was also among the first to notice how the Boomers announced their causes on their T-shirts as advertisements for themselves.

Marty has always been quick to notice the unnoticed deserving of attention. At more than one media gathering, I have seen him deflect a question he could have easily answered himself to someone else as a way of introducing an up-and-coming academic to reporters. Unlike a lot of public intellectuals, he feels absolutely no need to put his immense learning on display. Even in smaller, social settings, Marty instinctively notices whenever the conversation leaves someone out. “Tell me three things I should know about you” is the usual gambit he uses to include the excluded. He does this because he genuinely wants to know. And he can do it because good notice-ers are almost always attentive listeners too. Or maybe it’s just the Lutheran pastor in him coming out.

Before Sightings there was Context, Marty’s eight-page newsletter published by the Claretian Fathers commenting on items he had noticed in the broad batch of magazines and newspapers delivered daily to his front door. And before Context there was M.E.M.O., his slyly named weekly column in The Christian Century. The impetus behind all three journalistic ventures was to locate religion within the nation’s public life. Fifty years ago, it was not always clear from reading the religion columns or pages of our daily newspapers that we cannot really understand religious figures, ideas, and movements in isolation from their social, cultural, political, and historical contexts. We writers on religion all read Marty and took heed.

One of the lessons I learned from reading Marty’s books—especially Righteous Empire, with its division between public and private Protestantism, and his three-volume Modern American Religion, which ends about the year (1964) I joined Newsweek as Religion editor—is this: always to make room in longer stories for the relevant historical context, lest we contribute to the plague of present-mindedness.

Asked how many volumes he has published, Marty simply says he’s written, edited, or co-authored about as many books as he is years old—which doesn’t leave a lot of room on the M-shelf of anyone’s personal library for other must-haves like Maritain, MacIntyre, Milosz, McGinn, Merton, and Meir. As for the books he has read, there’s no counting. But that could and should be said of his colleagues at the Divinity School.

For example: sometime in the 1980s, the Divinity School teamed up with Catholic theologians identified with Concilium, an international quarterly created after Vatican Council II, at a conference in Germany. (In those days, theological conferences were considered newsworthy.) Marty pulled me aside during cocktail hour to tell me how much he enjoyed team-teaching a course that semester with theologian David Tracy. “Every time I mention a book,” he marveled, “David has already read it.” After dinner, Tracy pulled me aside to tell me how stimulating it was teaching a course with Marty. This—I swear—is what he said: “Every time I mention a book, Marty has already reviewed it.”

Besides being a great notice-er, Marty was a champion multi-tasker well before there was such a word. At yet another conference, Marty was invited—as he often was—to sum up two days of speeches by a dozen scholars and twice that many comments by responders. Marty agreed to do it but asked to sit backstage with the journalists and, like them, follow the proceedings on in-house television. It wasn’t just that he liked our rakish company; he had a lecture of his own to write for a conference the following week at Southern Methodist University. So, he watched and he wrote and kibitzed with us, and then he went to the podium and gave a precise, 45-minute summary of what everyone had said.

Although I have been privileged to know Marty for more than half a century, there are still three things about him that I think all of us should know.

Does he really have a photographic memory?

How does he always make his lectures end precisely when his stopwatch tells him to?

Finally, there is the matter of his name. Throughout this brief appreciation I have referred to him as “Marty.” Everyone does. That’s what his wonderful wife, Harriet, calls him and that is how he signs everything but his checks. Like Elvis, he is instantly identifiable by a single name. But is “Marty” a diminutive of his first name, Martin, like “Billy” is for William Franklin Graham? Or is the Marty we know him by his last name, as “Dylan” is to Bob?

High time, Marty, you shared these secrets with us.

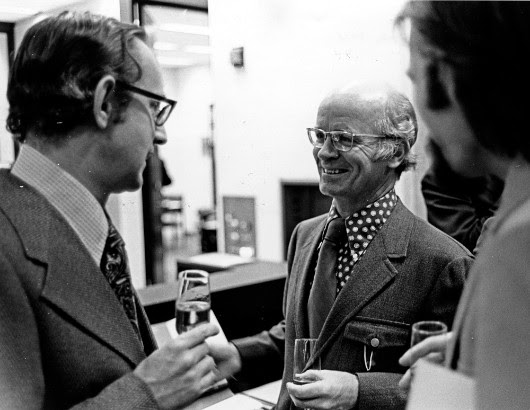

Image: Martin E. Marty (center) with other attendees at a 1974 exhibition on “The Tradition of Aquinas and Bonaventure” | Credit: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf3-00909, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

Author, Kenneth L. Woodward, is the former Religion editor of Newsweek. His most recent book is Getting Religion: Faith, Culture, and Politics from the Age of Eisenhower to the Era of Obama (Convergent Books, 2016). Author, Kenneth L. Woodward, is the former Religion editor of Newsweek. His most recent book is Getting Religion: Faith, Culture, and Politics from the Age of Eisenhower to the Era of Obama (Convergent Books, 2016). |

Sightings is edited by Brett Colasacco (AB’07, MDiv’10), a PhD candidate in Religion, Literature, and Visual Culture at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.