"The Latinx Vote" as Mission Field

The idea of the cultural homogeneity of Spanish-speaking immigrants to the US bears traces of missionary endeavors a century ago

Even before the end of this past election day, Patricia Mazzei, Glenn Thrush, and Giovanni Russonello wondered in the New York Times whether “Mr. Biden [did] too little, too late to court Latino voters?” Over the next few days many of their colleagues across the national media answered in the affirmative, and voiced concern and confusion over the apparent fact that Donald Trump performed better with Latinx voters than he had in the 2016. Much of the analysis focused on ethnically Mexican voters within the Mexico/US borderlands. In their election day article, Mazzei, Thrush, and Russonello vividly described the “labor intensive” work of persuading Latinxs to vote for Democratic candidate, now President Elect, Joe Biden in the terms of funds raised and spent, and the time Democratic operatives spent face-to-face with Latinx voters in the field. Such language—and with it, the conceptual framework underwriting the very category “Latinx”—carries striking echoes of how a group of missionaries described their own efforts along the Mexico/US border a century ago.

From its earliest days, the Assemblies of God (AG), founded in 1914 and now one of the largest Pentecostal denominations in the world, identified Spanish-speaking people living on the US side of the border as a promising mission field. At first, this field was simply called the “Mexican work.” White AG missionaries like H.C. Ball expressed a desire to actually missionize in Mexico, but, due to both the perceived dangers of the ongoing Mexican Revolution and intermittent legal restrictions on foreign missions in the Mexican state, they instead focused on the Spanish-speaking “Mexican” population on the US side of the border.

As these missionaries saw it, though, they were fortunate; the cities and towns on the US side were every day filling up with Mexicans whose migrations were, in one way or another, set in motion by the Revolution. These newly arriving Spanish speakers were for the most part ethnically Mexican, but almost certainly not all were; some were probably Spanish-speaking Native Americans, and a few may have originally been from Central and South America or the Caribbean. Even more, there were considerable, generations-old communities of Spanish-speakers, with their own distinct regional cultures and histories, living in what had only become the US side of the borderlands some sixty years earlier.

To make things even more complicated, early AG commentators and missionaries occasionally spoke of a general “Spanish work” which combined the border-focused “Mexican work” with burgeoning missions to Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico and New York City, as well as a few general “Spanish” missions throughout California. By the mid-1920s, white AG missionaries and readers of the AG newspaper had some sense of a generalized Hispanic mission field—and therefore Hispanic people—that was spatially internal to the US, but nevertheless peripheral and foreign. Perhaps as missionaries are wont to do, early AG evangelists made great efforts at trying to understand and appeal to these internal Spanish-speaking outsiders. Yet these efforts were frequently undercut by the presumptive and quasi-racial generalizations that allowed such distinct groups to be collated under the missionary taxon “Spanish.”

It is hard not to notice a disturbing continuity between early Pentecostal missions and national politics in election years like this one. The missionaries become campaigners and political action committees, their denominational press becomes cable news, and their “Spanish” targets become “Latinx voters.” Even though we didn’t know who had won by the end of this past election day, we were quickly informed that something strange, or at least unexpected, had happened with the Latinx vote: “they” had voted for Donald Trump at a higher percentage than “they” had in 2016.

That narrative was quickly challenged by a range of commentators and journalists, especially Latinx ones. They’ve reminded us that, while Latinx can be an important category of identity in the United States, it encompasses a range of communities which differ from one another in profound ways. Catholic Cubans in Miami have different ways of knowing and being in the world than Charismatic and Evangelical Mexicans in McAllen, Texas, or Tejano voters in Zapata, Texas. Their decisions on election day reflect this. Despite the fresh iteration of this reminder, though, the white liberal political commentariat seems unable to let go of the idea that the “Latinx voter” is a meaningful category of persons who need to be converted, or at least have their faith revived.

It is true that early Pentecostal missionaries made great efforts trying to comprehend their “Spanish” targets in order to convert them, but in addition to the never-questioned assumption that the “Spanish” were a more-or-less homogenous people, Pentecostals, like so many Protestant missionaries of the time, never doubted that Pentecostalism would be a self-evidently superior way of life and therefore irresistible to their missionary targets. Alice Luce, co-founder of the “Mexican work” with Ball, routinely theorized the appeal of Pentecostalism to the “Mexicans” in the borderlands over what she considered “Roman” (i.e., Catholic) decadence and decay of the region. There is a concerning similarity between this paternalistic hubris and a contemporary one which makes it seem obvious to largely white publics how any given Latinx community should vote.

For their part, many early AG borderlands missionaries thought of themselves as quite successful: their “Spanish” tent revivals and prayer services were always well attended, and after only a few years they had established fairly regular congregations, some of which were quite sizeable. As scholars like Gastón Espinosa and Daniel Ramírez have shown, though, many Mexican converts to Pentecostalism in the borderlands quickly left white Pentecostal institutions, and formed their own far more successful ones.

Translated into the civil-religious terms of party politics, we might observe that Latinx communities often evade both parties’ totalizing schematics and predictions through participation in their own organizing channels that are fully capable of doing politics all on their own. For some, these channels include Pentecostal institutions that are a legacy of both early AG missionaries and Mexican Pentecostals who rejected the AG’s white supremacy. Thus, a general faith in the goodness of what can only fairly be characterized as a historically white party, coupled with a paradigm that makes non-white people with disparate identities, religious traditions, communities, histories, and ties to places spanning two continents into a single ethnicity, risks misunderstandings and overestimations of either party’s appeal and successes.

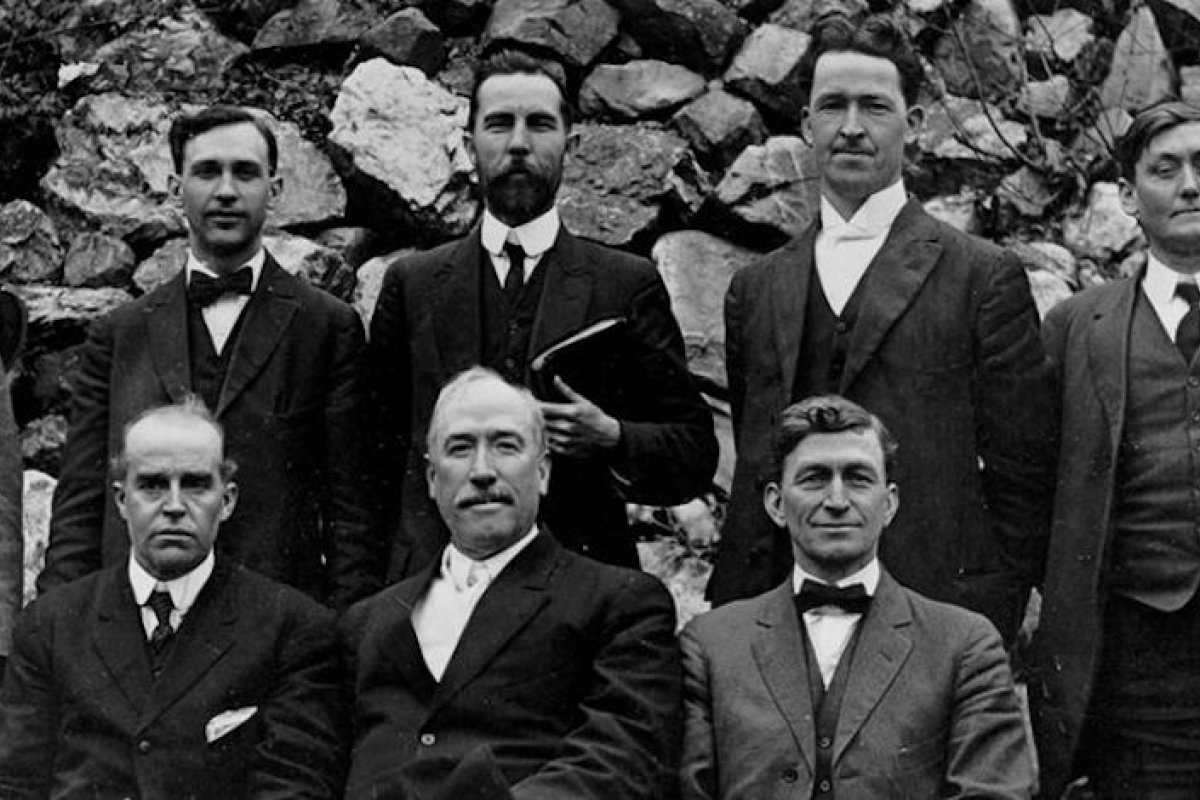

Photo: Members of the Assemblies of God Executive Presbytery, 1914 (AG News)

Sightings is edited by Daniel Owings, a PhD Candidate in Theology at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.