General Suleimani, U.S. Policy, and Jus ad Vim

Why we need a better way of talking about the use of “force short of war”

The killing of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani by U.S. forces may be discussed in legal, moral, strategic, and other terms. I propose to focus on moral issues, specifically in terms of the type of vocabulary we might use in evaluating this most recent development in U.S. relations with the Islamic Republic of Iran. In particular, I want to take this as an opportunity to consider a recent proposal to revise or otherwise extend the just war tradition by way of an account of what a number of scholars are calling jus ad vim—that is, a theory of (or at least an account of issues connected with) the use of force short of war.

The idea seems to be recent, with many publications tracing its origin to Michael Walzer’s 2006 preface to the fourth edition of Just and Unjust Wars, and specifically to his analysis of the policies by which the U.S. and its allies sought to contain Iraqi forces following the Gulf War. These included an embargo on imports of military equipment, regular inspections of weapons facilities by international representatives, and the establishment of no-fly zones designed to protect the Shi`a in southern Iraq and the Kurdish areas in the north. These are all actions of the type associated with war. And yet, most people would not have spoken about the containment of Iraq in that way—at least not if they were considering it in relation to the damage inflicted on Iraq’s infrastructure during the Gulf War, or even more so following the 2003 war to bring about regime change. We need a way to talk about cases like the containment of Iraq, wrote Walzer. We need a theory of jus ad vim.

These brief remarks inspired a vigorous and ongoing conversation, not least around the question of whether such a novel theory is really necessary. Then, too, one can find a lot of argument around the issue of what counts. After all, states routinely implement policies designed to affect the behavior of others. At what point do such efforts qualify as “force short of war”? If loan guarantees come with conditions, does that count? What about the imposition of tariffs or economic sanctions?

However one answers such questions, it does seem that the contest between the U.S. and the Islamic Republic fits the category. Perhaps we should take a longer view, but for now it will suffice to consider developments since May 2018, when President Trump announced a withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (also known as the “Iran nuclear deal”). Shortly thereafter, the U.S. renewed sanctions aimed at Iran’s economy; once these began to work, the Islamic Republic interfered with shipping in the Gulf, attacked Saudi oil facilities, and undertook other actions designed to alter American behavior. For the most part, U.S. response continued to focus on isolating Iran economically. Attacks on American assets in Iraq led to something different, however: a strike against Shi`i militias and then the targeted killing of General Soleimani. Clearly, we are not yet at war, and both sides express a desire to avoid that outcome. We are in a situation where the actors make use of force for political purposes, however; and thus, something like Walzer’s jus ad vim may provide us with a vocabulary for analysis.

So what is that vocabulary? The scholarly literature referenced above is quite diverse on this matter. One way to start is to ask about the relationship between just war tradition and jus ad vim. The former offers a familiar framework for thinking about resort to and conduct of war: the criteria of jus ad bellum, including legitimate authority, just cause, and right intention (this last one demonstrated by conduct consistent with the aim of peace, overall proportionality, reasonable hope of success, and last resort); and of jus in bello (discrimination, in the sense of avoiding attacks on civilian targets, and proportionality of means—that is, using only those amounts of force necessary to obtain a military objective). Some developers of jus ad vim suggest these criteria have limited utility for their purposes. That is not Walzer’s approach, however; and on this I agree with him. Even the criterion of last resort, which marks a kind of threshold between war and not-war, seems to function for jus ad vim, as it calls us to distinguish actions that bring us closer to war from those that do not—as, for example, in the case that is our current concern.

To put this another way, one of the special emphases of jus ad vim has to do with worries about the escalation of risk. What one wants is a vocabulary that attends to the possibility that a particular course of action may in fact make war more likely, rather than less. If force short of war is to be considered just or right, the aim ought to be to persuade a state to alter offensive behavior without resorting to the more expansive and destructive form of conflict we associate with war. The task of policymakers thus entails judgment: too little force simply encourages bad international actors, while too much runs the risk of a wider conflict.

This, it seems, is precisely what is at stake in the killing of Qassem Soleimani. In ordering this strike, the President and his advisers raised the level of U.S. response to Iranian provocation. In so doing, they hoped to change a rival’s behavior. At present, however, this seems unlikely. At this point, the death of Soleimani seems to have renewed Iranian national feeling; as well, the fact that he was killed on Iraqi soil has led to increased anti-American sentiment in that country. Of course, we do not know all the options available to American officials involved in discussions about Iran and our policies there at this or any other moment. But the strong reaction from Iranian officials suggests that something less sensational would have been preferable. Yesterday's apparent easing of tensions between the U.S. and Iran is good news, but the levels of force to be used on both sides of this contest may well still increase, and thus make war more likely. ♦

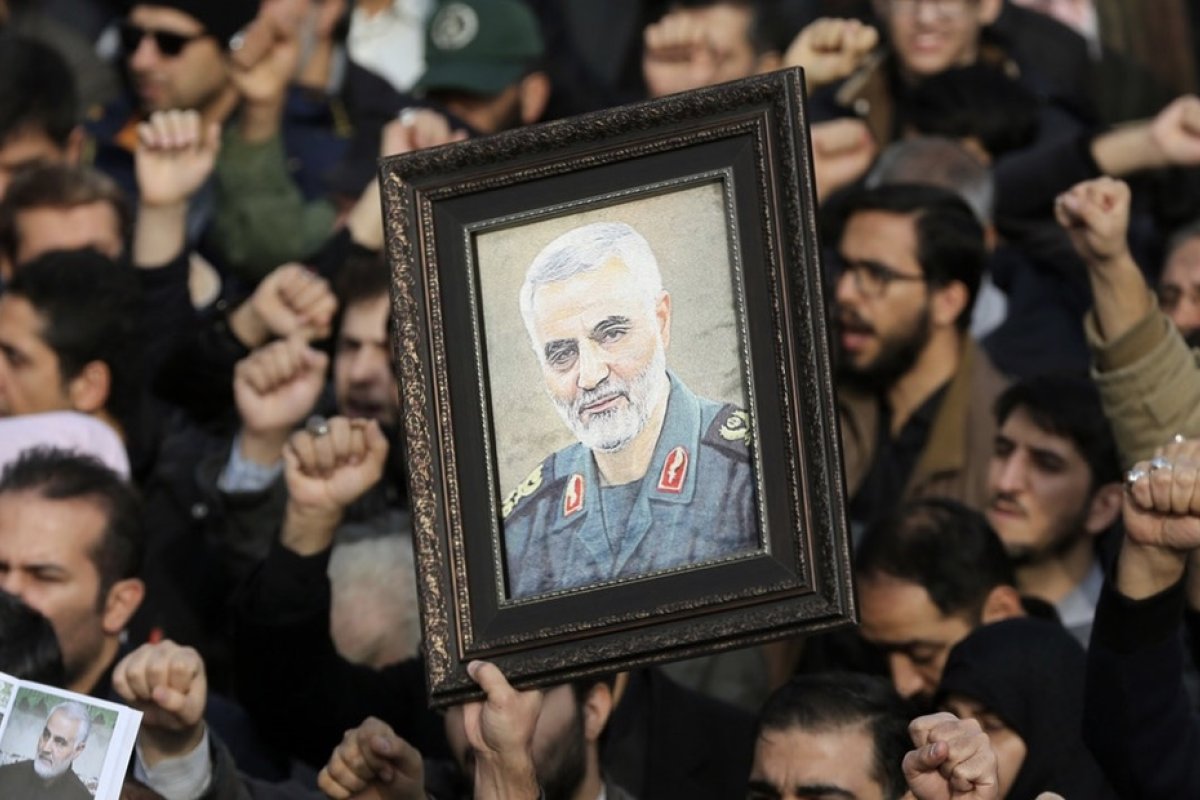

Image: Iranians gather to protest against the killing of Major General Qassem Suleimani after Friday prayer in Tehran on January 3, 2020. (Photo: Fatemeh Bahrami)

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.