A Summer Correspondence

The decision to rename a dormitory reveals the fragility of historical nuance

By Richard A. RosengartenSeptember 21, 2020

This August a dormitory at Loyola University in Maryland that had been named in honor of the American short story writer and novelist Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964) was renamed in honor of Sister Thea Bowman by the President and Trustees of the University. In a letter issued by President Brian Linnane, S.J., Loyola explained that its action responded to “information coming forward recently … that has revealed that some of her personal writings reflected a racist perspective.” “A residence hall must be a home and a haven for those who live there,” the letter explains, “and its name should reflect Loyola’s Jesuit values.”

Linnane’s letter concludes by noting that Sister Thea was “a Servant of God whose cause for canonization has been endorsed by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops,” that she was the granddaughter of slaves, and that she was a member of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration who “inspired people to work to eliminate racism and work for justice and served as an important voice within the Catholic Church in the United States during the twentieth century.”

Fr. Linnane was subsequently the recipient of a letter signed by over one hundred people, most of them scholars who write and teach about Flannery O’Connor, protesting the decision. (In the interests of full disclosure, I did not sign the letter.) Spearheaded by Angela Alaimo O’Donnell of Fordham University, the letter is limned by two quotes of approbation for O’Connor from the novelist Alice Walker (who was also a signatory).

Prior to Loyola’s announcement, The New Yorker published an article by Paul Elie about O’Connor (“Everything That Rises” in the print version; retitled “How Racist Was Flannery O’Connor?” online). There Elie—whose previous publications discussing O’Connor do not explicitly address her racism—reflects that the recently published letters not included in the heralded collection, The Habit of Being, display explicitly racist statements and sentiments from O’Connor’s early life and that they bring into greater relief aspects of O’Connor’s earlier published correspondence that had been ignored or elided. Elie also selectively cites and engages O’Donnell’s recent book on the question of race in O’Connor.

Commonweal magazine subsequently published in tandem a lament of Loyola’s action by O’Donnell, and a brief defense of the decision by Cathleen Kaveny of Boston College. Both the lament for what happened and its defense struck me as entirely cogent; taken together, O’Donnell and Caveny seem to me to tell this story in its genuine complexity.

The conceit that it is a new discovery that Flannery O’Connor used racist epithets is inaccurate, and that this has only been made clear with the discovery of new correspondence at best disingenuous. The virtue of O’Donnell’s recent book is that it aims to reinvigorate a conversation that has been part of just about every class, conference, church meeting, and private discussion about O’Connor that I’ve participated in over the last thirty years. Frederick Crews’ review of the Library of America edition of O’Connor’s work published in 1990 is a particularly prominent and public example.

That stated, it needs immediately also to be said that a number of people—including members of O’Connor’s family and certain of her advocates—have glossed over, elided, obscured or even hidden the fact and the (admittedly complex) implications of Flannery O’Connor’s use of “the n- word” in her correspondence and her fiction. Sally Fitzgerald’s quasi-hagiographical editing of The Habit of Being (1979) contributed to this. And Fitzgerald is hardly alone: flash forward to a 2017 collection of essays on O’Connor—ten authors, 230 pages—and you will discover no sustained consideration of these disturbing facts.

As a wise and seasoned O’Connor scholar remarked to me several years ago, those who gloss over and elide O’Connor’s words do her the real disservice of accentuating her considerable virtues at the expense of recognizing her very real faults. This kind of selective reappropriation is dishonest. It is also not how O’Connor treated anyone else; and, on the evidence of her writing, it is not how she would have wished to be treated. Like all human beings, O’Connor prepared a face to meet the faces that she met. Her public face mixed withering directness, various registers of humor, and apparent guilelessness about her own opinions. That combination is not easily assimilated (and like any such sophisticated persona, actively resisted when encountered in an energetic and talented woman). It is entirely consonant with that persona to imagine that O’Connor would be chastened by the language of Loyola’s decision, because she loved and respected the Catholic Church and was deferential to its authority. She also would be sincerely admiring of Sister Thea Bowman who—as noted below—probably reflected conventions of behavior that O’Connor could acknowledge without qualification.

The answer, then, to the online title of Elie’s article is to say that O’Connor wrote about Black people the way she wrote about everyone (including “interleckchuls” and “white trash”). A closer look at the correspondence shows the difficulty of rhetorical questions about degrees of racism. So we read as O’Connor declines an invitation to meet James Baldwin in Atlanta, remarking that she might meet him in New York, but that their meeting would only be a circus in Atlanta. The prospect prompts her to remark on her dislike for the emergence of “the new Negro,” and the word “uppity” is all but present in her pithy dismissal. In the wider context of her writing, what O’Connor means is clear: Baldwin, in her judgment, writes and talks about what he does not know, like any Northerner who presumes to pontificate about the South. The fact that he is Black affords him no more right to do so than it would Norman Mailer. O’Connor seriously underestimated Baldwin, mangling a writer at least as complex as herself into a prototype that is ugly and racist. We also encounter O’Connor writing with measured respect of Martin Luther King, Jr., saying that he was doing what he had to do; turning again to the wider context of her correspondence, we know that someone who is doing what God has given them to do earns O’Connor’s highest praise. But it feels grudging, especially when we read O’Connor’s manifest enthusiasm for the young Cassius Clay. Clay’s parables and political pronouncements about Vietnam mesmerize her, and her approbation of him is well ahead of general public opinion; but she also wrote that he was “too good for the Moslems.”

This is its own kind of double-speak, and especially in this moment it can be only partially mitigated by the fact that it is direct and guileless. I suspect that the complaint protesting the presence of O’Connor’s name on the dormitory does not reflect a nuanced acquaintance with her letters; but I will also acknowledge that Fr. Linnane’s concern that dormitories serve as “home” and “haven” can be no small matter to Loyola as it seeks honor the Jesuit value of cura personalis. And I celebrate the elevation of Sister Thea Bowman – even as Loyola’s language extolling her strikes me as rendering her more a figurehead than the very real human being that I am sure she was. Meanwhile Flannery O’Connor should and doubtless will continue to be read, debated, and discussed—perhaps even on Loyola’s campus—maybe, just maybe in ways that give full weight to her writing, and our reading, in all their respective complexities.

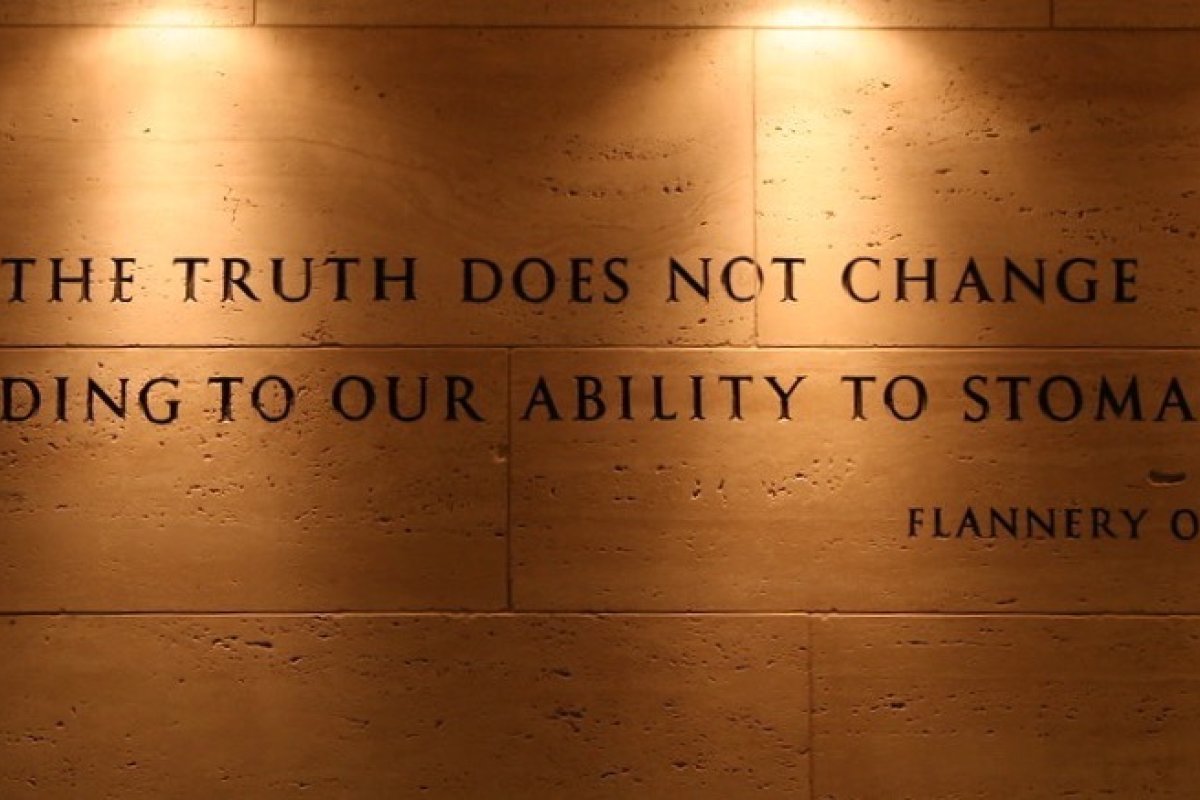

Image: Flannery O'Connor quote mounted in Tribune Tower, downtown Chicago. Photo courtesy of Brent D. Payne (edited). The quote is drawn from O'Connor's letter to "Miss A.," Sept. 6, 1955, and may be found on p.952 of the Library of America collection of her works.

Sightings is edited by Daniel Owings, a PhD Candidate in Theology at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.