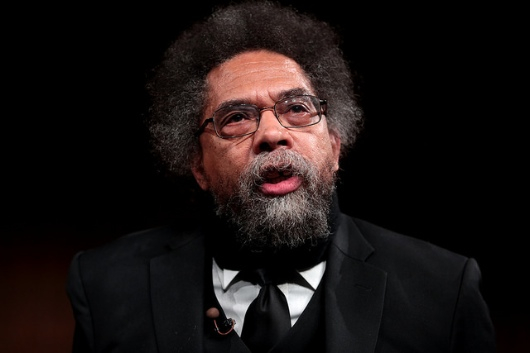

Cornel West and the Principle of Hope

It is worth taking the time to listen to W

By Foster J. PinkneyMarch 8, 2018

It is worth taking the time to listen to W. E. B. Du Bois’s words from his own mouth. There are dozens of examples on the web of Du Bois addressing the Negro problem, breaking down his Marxist analysis of slavocracy, or advocating for the unity of poor whites and the progeny of former slaves into a working-class revolutionary proletariat. What is most strange to modern ears is the hybridity of Du Bois’s accent. We can hear the slightly rolled “r” of a Mid-Atlantic accent, the large “o” and clipped endings which almost sound German, and the occasional upper-crust Southern pronunciation of common phrases reminiscent of Du Bois’s time at Fisk. The patrician air of his mannerisms, with its underlying sense of Victorian principles and Black cultural striving, speak to Du Bois’s abiding love for Black people and the possibilities of freedom within an American and global context.

It is worth taking the time to listen to W. E. B. Du Bois’s words from his own mouth. There are dozens of examples on the web of Du Bois addressing the Negro problem, breaking down his Marxist analysis of slavocracy, or advocating for the unity of poor whites and the progeny of former slaves into a working-class revolutionary proletariat. What is most strange to modern ears is the hybridity of Du Bois’s accent. We can hear the slightly rolled “r” of a Mid-Atlantic accent, the large “o” and clipped endings which almost sound German, and the occasional upper-crust Southern pronunciation of common phrases reminiscent of Du Bois’s time at Fisk. The patrician air of his mannerisms, with its underlying sense of Victorian principles and Black cultural striving, speak to Du Bois’s abiding love for Black people and the possibilities of freedom within an American and global context.

Cornel West speaks with a different voice to the same concerns. He too is concerned with the possibilities of emancipation and with democracy contextualized within an ethics of cultural and global redemption. West, however, loves blackness as much as he loves Black people. West celebrates the liminality and funk of Black existence which connects principled striving with a clear-sighted understanding of the moral dimensions of Black survival. The cadence of the Black gospel tradition combined with a street-level devotion to creativity define West’s voice. His commitment to fighting for justice defines West’s approach to activating scholarship and memory.

Du Bois loves Black people for what they can become when given the opportunities of autonomy; West loves Black people simply because they are and because blackness has created a culture of struggle with love at its center.

My first presentation to West was in his class on Du Bois at Union Theological Seminary over three years ago. I remember that day because I had to give my presentation on the first chapter of Souls of Black Folk with Harry Belafonte sitting directly behind me. After I was finished, West asked Belafonte if I had gotten the details of Du Bois’s personality correct—after all, he had met and spoken with the man many times. Belafonte said that I was close enough.

Belafonte was in New York at the time to go with West to a meeting with representatives from the emerging Movement for Black Lives—not simply to impart the wisdom of their experience to a young group of organizers, but also to listen and absorb the critique of those whose hopes and desires still centered on the possibilities of freedom.

West’s scholarship is always concerned with application, with the ability of academic work to engage with everyday struggles, reclaim memory from the abyss of white supremacist histories, and critique existing power structures in light of a prophetic truth which goes beyond superficiality to the roots of the human experience. Even when West overshoots his mark or overstates his case, we can always be sure that there is a principle of hope guiding his inquiry.

When West spoke on February 24 to a rapt audience in Rockefeller Memorial Chapel at the invitation of the University of Chicago Divinity School’s Ethics Club, his principle of hope was on full display. West’s commentary interwove the presentations given in honor of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication of Race Matters with a critique of neo-liberal consumerism, an explication of an American culture based in domination and displays of unchecked authoritarian violence, and a celebration of Black musical skill and imagination. A jazz-like free association of ideas and interplay of voices make West a provocative presence when engaged with an audience. His voice demands attention not only for its ability to convict, but also for its ability to reclaim the urgency of the American project.

Hope, for West, is always the product of community—of suffering and redemption seeking commonality in a shared vision of the future. Liberation ceases to be a mere possibility in the hands and strivings of an organized community seeking justice. Love becomes the grounding for democratic participation inclusive of all that is humanistic and generous. West is a catastrophic thinker always attentive to the reality of domination. The prophet sees within this reality the will of God working through hope and the communal realization of what can and should be. Cornel West is a prophet, and the principle of hope provides the imaginative tools of fightback against demonic forces of oppression. Or, as written by Paul, “I beseech you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, that ye present your bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable unto God, which is your reasonable service. And be not conformed to this world: but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind, that ye may prove what is that good, and acceptable, and perfect, will of God” (Romans 12:1-2, KJV).

Photo Credit: Gage Skidmore/Flickr (cc)

Author, Foster J. Pinkney, is a writer, organizer, and doctoral student at the University of Chicago Divinity School in the field of Religious Ethics. He received his MA in Social Ethics from Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York. Foster studies faith as it is reflected in the formation of values and ethical understandings of communal power. Author, Foster J. Pinkney, is a writer, organizer, and doctoral student at the University of Chicago Divinity School in the field of Religious Ethics. He received his MA in Social Ethics from Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York. Foster studies faith as it is reflected in the formation of values and ethical understandings of communal power. |

Sightings is edited by Brett Colasacco (AB’07, MDiv’10), a PhD candidate in Religion, Literature, and Visual Culture at the University of Chicago Divinity School.